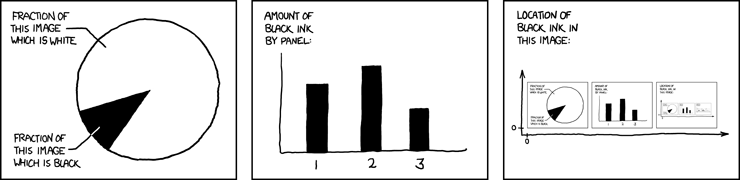

Before you embark on this journey of spontaneous cranial combustion, just remember that Randall Munroe, author of xkcd, was an engineer at NASA. Here we go (please click on it to see a bigger version. You're going to need detail for this):

Now, before you click your back button and scoff at the pointlessness of this strip, I urge you to read it a few times, and really think about it. Specifically, think about actually drawing the strip.

I'll give you a minute.

OK, this strip is an example of what we call self-referential recursion. Let's start with the self-referencing part.

Take this sentence: "This sentence has nine characters in it". True or false?

False, obviously. But now change the number so that the statement is true. It isn't easy. I don't think it's actually possible, and this is where the self-referencing part comes in. Read this rule slowly and carefully (lest you mind explode):

The amount of characters actually in the sentence is dependent on the amount of characters in the number of characters there are in the sentence.

Here's how it works. With no number in the sentence ("This sentence has characters in it"), it has twenty-nine characters. But once you put "twenty-nine" in the sentence, you've changed the amount of characters in the sentence, and it is false. The only way to make this true is to change the rest of the sentence around. Even then, it isn't a simple task.

Now, look at the first panel of the comic strip and see it with new understanding. And just in case you're a skeptic, the anally nerdy xkcd forum members have already proven the numbers to be accurate.

OK, got that? Now, off to the second panel. It's very similar in awesome-tude until you realize what's in store in the 3rd panel. Then you realize how much of a crazed genius this guy actually is. It's basically just a bar graph of the amount of black ink per panel, relative to the other panels. We already understand that this is quite complicated to determine, because it's self-referential and all three bars of the graph depend on how much black ink is in the graph itself. I'll let you mull over that one for a bit before we head into the recursion part of this little brain genocide of a webcomic.

OK, on to the third panel. On first glance, it seems a little pointless. He simply drew the strip again, and drew some lines outlining the location of the ink on the page. But now that we understand the point of the last two panels, the absurdity of this one isn't hard to spot. First of all, remember that it's self-referencing. In order for the second panel to be true,

the amount of black in the entire comic has to be already known before any of the panels are actually drawn, and the amount of black in the third panel is just a smaller proportion of the already known amount of black in the strip. Are you numb yet?

Because this only gets better.

Most people would simply stop there and bow in nerdy worship of the great and holy Randall, but they miss the final blow to your brain. There's still the recursion to deal with. Let's do this.

Put simply:

The entirety of the third panel is true.

In order to understand this, we need to go back to the first panel. The exact language was: The amount of black in the image. Not in the panel. In the entire strip. It's hard enough to understand when you realize how hard self-referencing calculation can be (which we just did), but the third panel just brings this into a whole new level.

The third panel is infinitely recursive. It contains images of itself, shrinking forever until you reach a number called 1/infinity (a fraction infinitely close to zero). The amount of black ink in each recursive image also shrinks, making a infinite summation. This means that you keep adding a smaller and smaller number to the previous number. For example, if the recursive term is 1/2, then the infinite summation of 1 over 1/2 is : 1 + 1/2 + 1/4 + 1/8 + 1/16 + 1/32 + 1/64 + 1/128 + .... etc. It ends up infinitely close to 2. This what we call the limit of the function f(x)=1/2y as x goes to infinity.

By the way, if you're still keeping up, we're doing calculus now. Be proud.

So, in order for that value in the pie slice of black to be true, it would have to be the limit of an infinite summation of the black ink in each recursion of the strip. So the first panel has to take into account the rate at which the third panel shrinks the strip and thus calculating the limit as the summation approaches infinity, and each "first panel" in the third strip also has to reflect the total proportion of black in the entire image, even as the values of black in each addition gets closer and closer to 1/infinity.

Also, notice that the first panel never mentions the actual amount of black. Only the amount of black in proportion to the amount of white. When it shrinks, the proportions hold true even though it talks about that black in the entire image, because it is a proportion and not a value. The second panel deals with the actual amount of black in each panel. Since it is a graphical representation and not numerical, and it references the black levels in each panel, it holds true in every recursion of the third panel. Thus, the third panel is always true, even as the images get smaller.

So, let's review:

- The strip accurately calculates (in black) the amount of black in the strip.

- This is called a self-referencing calculation.

- The total amount of black in the strip had to have been calculated and known before the strip was even created (i.e. you can't do this with trial and error), which is insanely insane (and redundant).

- Due to the nature of the third panel, the amount of black in the entire strip (which was known before the strip was made) is actually a value that represents the limit of an infinite summation of increasingly smaller values of black in every recursion, and thus, the slices of the pie chart also represent limits of infinite summations. (Read that a few times. Trust me, it makes sense)

- Every recursion of the third panel is true, because of the proportional nature of pie charts, and that graphical bar graphs can be shrunk proportionally and still be accurate.

- Oh, and like I said, analysis has already been done on the black levels in the strip, and it's eerily accurate.

Yes, this is what Randall Munroe finds funny.

And this is why I love xkcd.